I'm worried about the new Star Trek show, Strange New Worlds. And before I get into why, I want to be clear about something: it's not that I dislike Anson Mount's Captain Pike, or that I am immune to the delight in the premise. I've been yearning for Star Trek to get back to what I believe are its roots and its values, values I've found missing from Discovery thus far except inasmuch as Pike came into represent the optimism and compassion of the Federation in season 2.

I get why people are excited, on multiple levels. I even share some of that excitement--with trepidation born of my disappointment in other Goldsman and Kurtzman projects. Because Pike does represent the best of the Federation, he does embody what I think has been missing from the grimdark self-seriousness of Discovery, and I totally get the desire to return to that.

But something is bothering me, has been bothering me, since Pike (and Spock) first showed up. And that's this: that what originally felt like a bone thrown to the segment of fandom that wants to see old characters turn up overlaps with a virulent strain of bigotry I see every day online. Headline after headline crows that "fan demand" has brought Pike, Spock, and Number One to the screen on their own show. Fan after fan has posted about how great it is that we're finally getting back to what Star Trek is about. Post after post mentions how the viewer "couldn't get into Discovery until Pike."

Now, that's all well and good--we relate to what we relate to, and it's very true that Pike is a different side of Trek than we've seen lately. So that sentiment isn't off base. What I think is off base is the fact that the Powers that Be chose to represent What's Good About Star Trek by first bringing in a trio of white characters to embody true Starfleet values and then giving them their own show. There's an excusable version of this where you justify it via the original characters all being (or passing as) white, and Pike as an established captain of the Enterprise is going to have a certain standing and philosophy, so none of this is inherently rooted in bigotry, just as appreciating the characters or the new show is not.

However, and it's a big but in my opinion, it's an unfortunate move in a franchise that, of late, has done a much better job than previously about creating and casting characters of color and other minority groups. The move to give the three white guys their own show is not, in my opinion, inherently racist. But it does dovetail unfortunately with a vociferous group in fandom that hates Discovery and cannot give any name to their disgust other than "SJW propaganda" and "forced diversity," whatever that means. Speaking as someone who also dislikes Discovery, the only thing I do appreciate about it is the casting and characters. But when an opinion I see spouted literally every day on internet groups, that Star Trek has gotten "too diverse," or that the ONLY thing DISCO is here for is to cram minorities down our throats, the announcement that a trio of white throwback characters is getting a new show getting greeted with applause and acclaim feels like a vindication for that ugly segment of the population.

I don't know what exactly the solution is, not that I have any say in this. I don't think there's anything wrong with Strange New Worlds as a show, and I actually look forward to seeing what they do because again, I'm here for the optimism, not the teenage diary platitudes about how dark the world is. But I wish I could see this development as something other than a bowing down to the backlash against the noble but behind-the-times efforts Trek has been making of late. It feels, in a way, like going backwards.

I'm still waiting to go where no one has gone before, and that doesn't seem like what they're going for, here.

Where no (white) man has gone before?

Posted by Kris/Pepper at 12:24 PM Labels: fandom, star trek, tv

Masterlist of 24FlamesPerSecond Apperances!

Posted by Kris/Pepper at 2:22 PM Labels: film, podcasts

I like to talk about movies. Weirdly enough, someone allows me to sometimes do so in recorded form. 24 Flames per Second is a podcast with a "roasting" set-up: one person defends a beloved film, and two people debate them. Sometimes it's a better discussion than others, but I've been on quite a few at this point, so I'll collect 'em here in case anyone's ever interested.

Zombieland (co-hosting)

Beetlejuice (roasting)

Scream (roasting)

First Blood (roasting)

Moulin Rouge (roasting)

Jaws (co-host)

Clueless (co-host)

Maleficent (co-host)

Avengers: Infinity War (roasting)

Big (defending)

John Wick (roasting)

It's a Wonderful Life (defending)

Election (defending)

Labyrinth (roasting)

Spider-man: Homecoming (roasting)

Blade Runner (roasting)

The Last Jedi (roasting)

Captain America: Civil War (roasting)

Boogie Nights (roasting)

A Christmas Story (roasting)

The Birds (roasting)

Now, contrary to my customary role, I don't hate these movies. Well, I hate some of them. But it's about the debate, and I've roasted movies I love, movies I don't like, movies I thought I liked until I roasted 'em and convinced myself, and movies I think should die inna fire. I don't get to talk about film as much as I'd like, and this has become a wonderful outlet for that impulse!

Zombieland (co-hosting)

Beetlejuice (roasting)

Scream (roasting)

First Blood (roasting)

Moulin Rouge (roasting)

Jaws (co-host)

Clueless (co-host)

Maleficent (co-host)

Avengers: Infinity War (roasting)

Big (defending)

John Wick (roasting)

It's a Wonderful Life (defending)

Election (defending)

Labyrinth (roasting)

Spider-man: Homecoming (roasting)

Blade Runner (roasting)

The Last Jedi (roasting)

Captain America: Civil War (roasting)

Boogie Nights (roasting)

A Christmas Story (roasting)

The Birds (roasting)

Now, contrary to my customary role, I don't hate these movies. Well, I hate some of them. But it's about the debate, and I've roasted movies I love, movies I don't like, movies I thought I liked until I roasted 'em and convinced myself, and movies I think should die inna fire. I don't get to talk about film as much as I'd like, and this has become a wonderful outlet for that impulse!

Sherlockianiana (reflections from Left Coast Sherlock Symposium)

Posted by Kris/Pepper at 8:09 PM Labels: fandom, sherlock holmes

When I learned that there was a new Sherlock Holmes convention within spitting distance of Seattle, I was delighted. I was part of the late lamented Sherlock Seattle con committee, which sort of got me back into Sherlock Holmes fandom after a long absence. I joined because I thought there should be more representation of the older iterations in the BBC-focused con; now, I tend to be the voice for the new and the weird in our local scion meetings. So I was even more excited to be chosen as a speaker for LCSS, on the topic of acting and Sherlock Holmes. This was based on my debatable expertise as someone who's taught about Holmes on film and played him on stage a few times. But this entry is about my overall thoughts about the con, so I'll try to find a balance between meaningfully specific and concise.

Overall (for those who want the birds-eye view) I have to say that I am incredibly happy and impressed by the work done by the organizing team and I'm grateful for the fabulous attendees. The weekend went amazingly smoothly, the panels were a fabulous cross-section of the charmingly pedantic, obscure, socially conscious, and poetic sides of the fandom. The crowd was an admirable mix of what I'd term "old school" and internet-raised fans. And the general attitude was one of acceptance, of "big tent" Sherlockianism (in Tim Johnson's words), of joyous celebration. I usually come off of conventions feeling better about fandom than I did before, because it turns out that when you put a bunch of people who love the same thing in different ways into a room, the love usually wins out. I also want to say that I am flattered at being included; I've never given a solo talk at a convention like this, and I was in illustrious company I do not at all feel I am at the level of.

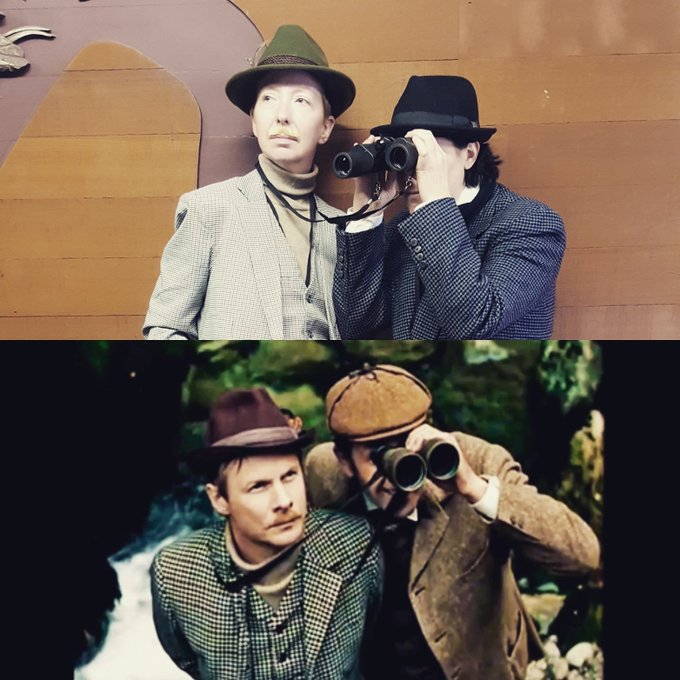

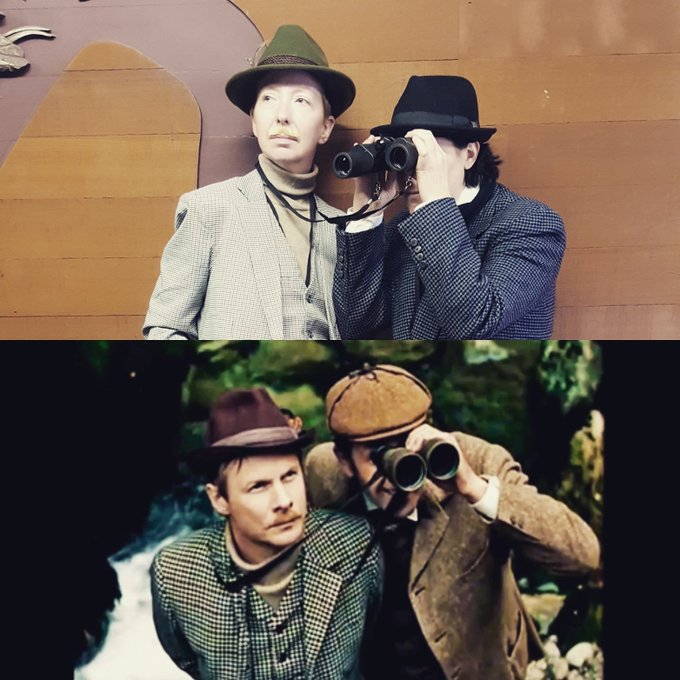

I drove down to Portland with my flatmate, Strangelock, which was emotionally significant for me because we met doing Sherlock Seattle and I feel that our partnership is very Holmes-and-Watson-ish. It's not that we break exactly on those lines, but there are more similarities than not, and so we celebrated that by dressing as the Lenfilm (Soviet) versions of the characters on Saturday.

Brad Keefauver has blogged way more articulately as I can about the specific panels, partly because he was basically live-blogging the whole way, but some thoughts.

Robert Perret's talk about the questionably scholarly nature of Sherlockian writings was a wonderfully nerdy meta-view of the fandom, which I love because it is an example of the thing it is studying, and I enjoy that kind of thing. Basically I would go to a thing about a thing every time, skipping the thing itself. Next, Sonia Fetherston & Julie McKuras presented a history of the women who have tried to break the glass ceiling of "official" Holmes society in the US which made me basically want to dig up all the past BSI dudes so I could punch them in the skull. Then, we had Chuck Kovacic's charming presentation on his recreation of the Baker Street sitting room. He has VERY strong opinions on how to do it right, and was a very entertaining speaker. Colebaltblue and Sanguinity's talk on Holmestice was mostly stuff I already knew, but here's the thing: I thought it was an incredibly valuable addition to the program. So many people long in the fandom are entirely unaware of a lot of the more recent innovations in fanworks and sharing, and these two managed to bridge that gap beautifully, in an unthreatening and inclusive manner. I think this morning really encapsulated so much that was great about this weekend: the fact that all ways of exploring Holmes are valid, and we can all contribute in our own style.

Speaking of which, next up after lunch were the fine gentlemen from BWAHAHAHA, demonstrating the style of pugilism that might have been described in Watson's writings. (Or rather, mostly by Holmes' description of his own prowess.) If you know me, you know I've dabbed in fencing and aerials and roller skating and all kind of things and I'm definitely going to hit up one of these practices to see how I like it. See again: doing a thing about a thing instead of the thing. If I'm practicing this HISTORY of a thing I'm more interested, for some reason. Next was Nancy Holder up with her presentation about Holmes in science fiction and horror, which was a great overview of the genre fiction our hero has taken part in. It's always made me slightly uncomfortable to combine Holmes with the supernatural, mostly because I like the LOGIC of the world that he represents, and a lot of the supernatural/horror stuff sort of throws all of that into question. But that's a post for another day, maybe. Our last stop of the day was with Dr. Bruce R. Parker on the use of medicine in the canon, which was really fascinating from the perspective of a doctor. I restrained myself and did NOT ask my question about BRAIN FEVER which is one of my favorite ailments of all time, mostly because when you look it up online it's basically only... references to ACD stories.

All in all, a very satisfying day. We had some time before the banquet, and strangelock wasn't going, so we walked downtown to Powell's books and got dinner and got back in time for me to put my mustache back on and mosey on down to the banquet. Having already eaten, I caught up with some of my fellow SOBs and took in the magic show. True to my nature, I enjoyed it more than I expected because it wasn't just a magic show; it was a treatise on centuries-old conjurer gossip. The history of conjuring was just as interesting as the effects themselves.

Day two was the big day, the day of my own presentation. I dressed in a slightly more modern dapper mode, sans facial hair, and placed myself next to Brad at what we deemed the speakers' table, though it was really just half the speakers. Side note: I was so excited to finally meet Brad Keefauver. I first encountered him in 1994 in the message boards of *Prodigy, which was the home of the Wigmore Street Post Office. I still have numerous copies of that zine, where I appear alongside Brad and Lee Shackleford and other greats of the fandom. I brought one with me, for him to sign, which he graciously did, but I cannot even express how gratifying it was to meet in person one of those who accepted a weird 14 year old into one of the oldest fandoms in the world.

First came the raffle, in which I won nothing, and then it was Lyndsay Faye's turn to speak about pastiche and fanfiction and the use of Sherlock in various works. I loved the idea that all novels are sequels, that we're all just riffing off what came before, because I truly believe it. The theme of the day, I think, was "All Holmes is Good Holmes," Lyndsay set us up well with her examination of how we all write the book we want to read, and it's all okay. Nothing erases what you love about the character, and there is room for all of it.

Here's the part where it gets bleak, for me, but transcendent. Tim Johnson of the U of Minnesota delivered a prose poem that covered not just his relationship to Sherlock Holmes and his fandom over the years, but beautifully evoked the way that fandom needs to encompass all visions. I cannot come close to doing it justice, but to hear a man so steeped in the history of this character and fandom make a plea for understanding and inclusion literally made me cry. The standing ovation was the only one of the weekend, and it could not have been more deserved. He was an inspiration.

I was next, and I was devastated to go after Tim, but I spoke a bit about the history of Sherlock on film and about the ways he can be portrayed. I was trying to do something that 1) I hadn't seen done before and 2) combined my dual tracks of studying Holmes on film and playing him on stage. So I basically tried to get people thinking beyond terms of "this is my favorite" into the question of what are they doing? that works (or doesn't) for various people. It seemed well-received! And I enjoyed the comments immensely.

Last but certainly not least (and as I joked in my talk, I was glad he was after me so everyone had stuck around), was Brad Keefauver with his multiverse theory of Sherlock Holmes. It's an attempt to make all versions "true," the idea being that each discrepancy is actually a branched universe. I love this, and it dovetails neatly with the big tent plea of Tim Johnson and the all stories are sequels statement from Lyndsay Faye. I like to think my points fall in there, too, in the sense that I was talking about the multiple "right" ways of being Holmes, and the way those techniques will work on some and not all but it's not objective.

With that, the symposium was over, and after a late lunch at my favorite restaurant in Portland (Nicholas Restaurant, best pita and hummus anywhere) strangelock and I drove home. I don't know where my next fandom adventure lies, but I know I want it to be alongside these people, and I hope if they're reading this they'll stay in touch. All Holmes is Good Holmes, and getting to share him with a room full of like-minded but utterly different fans was a reminder of how rich this fictional life is.

Overall (for those who want the birds-eye view) I have to say that I am incredibly happy and impressed by the work done by the organizing team and I'm grateful for the fabulous attendees. The weekend went amazingly smoothly, the panels were a fabulous cross-section of the charmingly pedantic, obscure, socially conscious, and poetic sides of the fandom. The crowd was an admirable mix of what I'd term "old school" and internet-raised fans. And the general attitude was one of acceptance, of "big tent" Sherlockianism (in Tim Johnson's words), of joyous celebration. I usually come off of conventions feeling better about fandom than I did before, because it turns out that when you put a bunch of people who love the same thing in different ways into a room, the love usually wins out. I also want to say that I am flattered at being included; I've never given a solo talk at a convention like this, and I was in illustrious company I do not at all feel I am at the level of.

I drove down to Portland with my flatmate, Strangelock, which was emotionally significant for me because we met doing Sherlock Seattle and I feel that our partnership is very Holmes-and-Watson-ish. It's not that we break exactly on those lines, but there are more similarities than not, and so we celebrated that by dressing as the Lenfilm (Soviet) versions of the characters on Saturday.

Brad Keefauver has blogged way more articulately as I can about the specific panels, partly because he was basically live-blogging the whole way, but some thoughts.

Robert Perret's talk about the questionably scholarly nature of Sherlockian writings was a wonderfully nerdy meta-view of the fandom, which I love because it is an example of the thing it is studying, and I enjoy that kind of thing. Basically I would go to a thing about a thing every time, skipping the thing itself. Next, Sonia Fetherston & Julie McKuras presented a history of the women who have tried to break the glass ceiling of "official" Holmes society in the US which made me basically want to dig up all the past BSI dudes so I could punch them in the skull. Then, we had Chuck Kovacic's charming presentation on his recreation of the Baker Street sitting room. He has VERY strong opinions on how to do it right, and was a very entertaining speaker. Colebaltblue and Sanguinity's talk on Holmestice was mostly stuff I already knew, but here's the thing: I thought it was an incredibly valuable addition to the program. So many people long in the fandom are entirely unaware of a lot of the more recent innovations in fanworks and sharing, and these two managed to bridge that gap beautifully, in an unthreatening and inclusive manner. I think this morning really encapsulated so much that was great about this weekend: the fact that all ways of exploring Holmes are valid, and we can all contribute in our own style.

Speaking of which, next up after lunch were the fine gentlemen from BWAHAHAHA, demonstrating the style of pugilism that might have been described in Watson's writings. (Or rather, mostly by Holmes' description of his own prowess.) If you know me, you know I've dabbed in fencing and aerials and roller skating and all kind of things and I'm definitely going to hit up one of these practices to see how I like it. See again: doing a thing about a thing instead of the thing. If I'm practicing this HISTORY of a thing I'm more interested, for some reason. Next was Nancy Holder up with her presentation about Holmes in science fiction and horror, which was a great overview of the genre fiction our hero has taken part in. It's always made me slightly uncomfortable to combine Holmes with the supernatural, mostly because I like the LOGIC of the world that he represents, and a lot of the supernatural/horror stuff sort of throws all of that into question. But that's a post for another day, maybe. Our last stop of the day was with Dr. Bruce R. Parker on the use of medicine in the canon, which was really fascinating from the perspective of a doctor. I restrained myself and did NOT ask my question about BRAIN FEVER which is one of my favorite ailments of all time, mostly because when you look it up online it's basically only... references to ACD stories.

All in all, a very satisfying day. We had some time before the banquet, and strangelock wasn't going, so we walked downtown to Powell's books and got dinner and got back in time for me to put my mustache back on and mosey on down to the banquet. Having already eaten, I caught up with some of my fellow SOBs and took in the magic show. True to my nature, I enjoyed it more than I expected because it wasn't just a magic show; it was a treatise on centuries-old conjurer gossip. The history of conjuring was just as interesting as the effects themselves.

Day two was the big day, the day of my own presentation. I dressed in a slightly more modern dapper mode, sans facial hair, and placed myself next to Brad at what we deemed the speakers' table, though it was really just half the speakers. Side note: I was so excited to finally meet Brad Keefauver. I first encountered him in 1994 in the message boards of *Prodigy, which was the home of the Wigmore Street Post Office. I still have numerous copies of that zine, where I appear alongside Brad and Lee Shackleford and other greats of the fandom. I brought one with me, for him to sign, which he graciously did, but I cannot even express how gratifying it was to meet in person one of those who accepted a weird 14 year old into one of the oldest fandoms in the world.

First came the raffle, in which I won nothing, and then it was Lyndsay Faye's turn to speak about pastiche and fanfiction and the use of Sherlock in various works. I loved the idea that all novels are sequels, that we're all just riffing off what came before, because I truly believe it. The theme of the day, I think, was "All Holmes is Good Holmes," Lyndsay set us up well with her examination of how we all write the book we want to read, and it's all okay. Nothing erases what you love about the character, and there is room for all of it.

Here's the part where it gets bleak, for me, but transcendent. Tim Johnson of the U of Minnesota delivered a prose poem that covered not just his relationship to Sherlock Holmes and his fandom over the years, but beautifully evoked the way that fandom needs to encompass all visions. I cannot come close to doing it justice, but to hear a man so steeped in the history of this character and fandom make a plea for understanding and inclusion literally made me cry. The standing ovation was the only one of the weekend, and it could not have been more deserved. He was an inspiration.

I was next, and I was devastated to go after Tim, but I spoke a bit about the history of Sherlock on film and about the ways he can be portrayed. I was trying to do something that 1) I hadn't seen done before and 2) combined my dual tracks of studying Holmes on film and playing him on stage. So I basically tried to get people thinking beyond terms of "this is my favorite" into the question of what are they doing? that works (or doesn't) for various people. It seemed well-received! And I enjoyed the comments immensely.

Last but certainly not least (and as I joked in my talk, I was glad he was after me so everyone had stuck around), was Brad Keefauver with his multiverse theory of Sherlock Holmes. It's an attempt to make all versions "true," the idea being that each discrepancy is actually a branched universe. I love this, and it dovetails neatly with the big tent plea of Tim Johnson and the all stories are sequels statement from Lyndsay Faye. I like to think my points fall in there, too, in the sense that I was talking about the multiple "right" ways of being Holmes, and the way those techniques will work on some and not all but it's not objective.

With that, the symposium was over, and after a late lunch at my favorite restaurant in Portland (Nicholas Restaurant, best pita and hummus anywhere) strangelock and I drove home. I don't know where my next fandom adventure lies, but I know I want it to be alongside these people, and I hope if they're reading this they'll stay in touch. All Holmes is Good Holmes, and getting to share him with a room full of like-minded but utterly different fans was a reminder of how rich this fictional life is.

She's the Man

Posted by Kris/Pepper at 4:01 PM Labels: gender, theater

The other day, I waded into an online argument I knew would not result in any changed minds or new understanding. It was about whether a certain character ‘should’ or ‘could’ be played by a woman instead of a man, with the arguments mostly boiling down to, “it would change the entire storyline,” sometimes with a side of, “...because you’d have to recast all the other characters as the opposite gender.”

As someone who’s made a routine of playing a gender onstage other than the one I pass for in real life, this was, of course, of interest to me. I am actually more often analyzing this from the other side--is it, in fact, politically correct for a cis-woman to portray a man, or is that verging into trans-appropriation? I don’t, any more, thinking about it from the probably more conventional side of “can a woman realistically play a male character or is it inherently an exercise in dancing dogs?”

As someone who’s made a routine of playing a gender onstage other than the one I pass for in real life, this was, of course, of interest to me. I am actually more often analyzing this from the other side--is it, in fact, politically correct for a cis-woman to portray a man, or is that verging into trans-appropriation? I don’t, any more, thinking about it from the probably more conventional side of “can a woman realistically play a male character or is it inherently an exercise in dancing dogs?”In some ways this is a complicated question with a lot of nuance and angles to examine. (What makes gender? How it is divorced from sex, if at all? Are there characters and character traits which are unconvincing in a person of the opposite gender? Is it different because I’m a woman playing a man, instead of the other way around, and why?) In another sense, it feels like simplicity itself--this is acting, you’re suspending disbelief anyway, we all know I’m not a Jedi or a starship captain so what difference does it make what parts I have under my clothes?

There are a lot of reasons I like playing men. Some are selfish, and possibly touch on internalized misogyny: my favorite characters (and lots of leads) are men, so if I didn’t play a man I wouldn’t get to be the captain, the hero, the detective. Some are personal: I have never quite felt comfortable calling myself female, though I’ve been one long enough that I don’t feel comfortable saying I’m anything else, and one of my bulletproof narrative kinks has always been girls-dressed-as-boys because I relate to it. My third reason is slightly political, though I have never really seen it as all that revolutionary: I want people to look at me on stage and say, “well why can’t Captain Kirk be played by a woman?”

In doing so, I’m not really saying that the next film should have Kristen Bell dressed as a boy and answering to “Jim.” Though I’d be ok with that, too. When I’ve played men, both in my own theater company and elsewhere, we’ve left pronouns alone and dressed me as a man, however. And I think it’s because I want the question to be one the audience asks itself. Does it matter? Does the love interest have to change gender? Is the story “different” because I’m a woman?

It’s also not that I think there isn’t a difference between my performance and, say, William Shatner or Jeremy Brett. But I think my being shorter, or having a higher voice, or being blonde, are just as significant. Some of those things do have to do with typical feminine physical traits, sure. But what exactly are people citing when they say that “James Bond could never be a woman”? Are they saying that no woman could possibly possess the abilities he does? Or the charisma, sexual appetite, or confidence? Or do they actually mean that they do not or cannot accept a woman in that role due to their own feelings about male and female roles in society?

I definitely don’t automatically think that anyone who thinks James Bond can’t be a woman is consciously applying misogyny. In this recent argument, I heard a lot of “I believe women and men are equal, I just don’t think a woman would be convincing as X.” And maybe they believe that. But when I play a man, what I hope the audience is doing is addressing their own preconceptions about what a “woman” and a “man” are, and if they come to the conclusion that I am unconvincing, at least maybe they have a more coherent argument as to why.

I definitely don’t automatically think that anyone who thinks James Bond can’t be a woman is consciously applying misogyny. In this recent argument, I heard a lot of “I believe women and men are equal, I just don’t think a woman would be convincing as X.” And maybe they believe that. But when I play a man, what I hope the audience is doing is addressing their own preconceptions about what a “woman” and a “man” are, and if they come to the conclusion that I am unconvincing, at least maybe they have a more coherent argument as to why.There is a lot more I could say about this, and I hope to continue this discussion with anyone who cares to. But I will leave it here, for now, as a first attempt at exploring a topic near and dear to my heart. I will continue to audition for and to cast men, women, and non-binary folk in my shoes just as I will cast all ethnicities and physical abilities--in any role to which they are suited, regardless of these factors. Because I think this conversation is important to have, and because I think we need to analyze why we put some character and personality traits in gendered baskets that don’t seem terribly applicable to real life.

Real Person Fic: not just for tumblr. Ever, really.

Posted by Kris/Pepper at 3:32 PM Labels: fandom, film history

Man years ago, while exploring a warren of a used bookstore in Kutztown, PA, I came across two volumes of Hollywood RPF. Two flaking, bound volumes from 1942-43:

Ginger Rogers and the Riddle of the Scarlet Cloak by Lela E. Rogers, and

Betty Grable and the House with the Iron Shutters by Kathryn Heisenfelt.

What is RPF, you may well ask?

RPF stands for "real person fanfiction," a subset of fanfic which, instead of fictional characters, takes as its subjects actual people, usually celebrities. In the past few decades there's been a lot of angst in fan communities about the ethics of this sort of activity, and the degree to which it violates an actor or musician's right to privacy. What's fascinating about this find is the reminder that, well, it's been around a lot longer than fanfiction.net.

So what are these books like? The full text of title page for the Ginger Rogers one continues:

An original story featuring

GINGER ROGERS

famous motion-picture star

as the heroine

By LELA E. ROGERS

Illustrated by Henry E. Vallely

Authorized Edition

WHITMAN PUBLISHING COMPANY

RACINE, WISCONSIN

The verso includes: Except the authorized use of the name of Ginger Rogers, all names, events, places, and characters in this book are entirely fictitious.

I was, understandably, fascinated, so I bought them both, put them on my shelf, and promptly forget about them. Until now. Looking at them, they're that very lightweight, cheap sort of thing that I doubt would have held up in a library setting for long. I do wonder where these copies came from. (Betty Grable shows 38 copies on www.abe.com, from $3.00 to $78.97; Ginger Rogers shows 63 copies from $2.15 to $110.12, if you're curious.) The back pages list charming titles from the same publisher, segregated for girls and boys, though the page of interest reads thus:

WHITMAN AUTHORIZED EDITIONS

NEW STORIES OF ADVENTURE AND MYSTERY

Up-to-the-minute novels for boys and girls about Favorite Characters, all popular and well-known, including--

Ginger Rogers and the Riddle of the Scarlet Cloak

Deanna Durbin and the Adventure of Blue Valley

Deanne Durbin and the Feather of Flame

Ann Rutherford and the Key to Nightmare Hall

Blondie and Dagwood's Secret Service

Polly the Powers Model: The Puzzle of th Haunted Camera

Jane Withers and the Hidden Room

Bonita Granville and the Mystery of Star Island

Joyce and the Secret Squadron: A Captain Midnight Adventure

Nina and Skeezix (of "Gasoline Alley"): The Problem of the Lost Ring

Red Ryder and the Mystery of the Whispering Walls

Red Ryder and the Secret of Wolf Canyon

Smilin' Jack and the Daredevil Girl Pilot

April Kane and the Dragon Lady: A "Terry and the Pirates" Adventure

(It also mentions that "The books listed above may be purchased in the same store where you bought this book." Oh, if only that were true! Note, by the way, the fact that actresses, not the roles they play, share "Favorite Character" status with comic strip figures. In the case of most of these stars, that's probably fairly accurate.)

This website has a complete listing of the actress titles, which also include Judy Garland, Shirley Temple, Gene Tierney, and Dorothy Lamour. It also reveals that Lela E. Rogers was Ginger's mother, and lots of other stuff I don't have access to, like general information about the writing and the way in which the "real person" angle is handled. According to the site, Heisenfelt wrote half the books, all of which "read like parodies of series books":

Heisenfelt's characters nearly always encounter one or more people who are stricken by fear that is superstitious. The heroine is usually fearful as well, with the difference being that the heroine is able to control her fear enough not to make a complete fool out of herself. Every event in the story has a mysterious importance, and normal, everyday sounds, such as a shutting door or a cat's meow, are often taken to be extremely scary. The mystery usually turns out to be a fairly insignificant mystery, and in some cases would not have been a mystery had everyone communicated with each other. In short, Heisenfelt's books tend to be overly-dramatic. The entire plot of each Heisenfelt book usually occurs in a very short period of time, often in fewer than 24 hours.

It also explains that there are two groups of stories in this loosely-defined "series": books in which the main character is in fact the actress named, and "while the heroine is identified as a famous actress, the stories are entirely fictitious and center around a mystery that convenient appears while the heroine is briefly visiting a dear friend. In some of these stories, many of the other characters fail to recognize the actress in spite of her openness about her identity!" The others are adventures where the character has the same name and looks as the actress but is, in fact, just a regular girl. Since I have one of each here, I'll see what I can see without actually reading them cover to cover.

Betty Grable and the House With the Iron Shutters

The story opens:

An April sun which had made several ineffectual attempts to appear from behind a bank of sullen clouds met suddenly with a measure of success. Long streamers of light penetrated the mended laces of a tall window, twining in a caressing halo on the golden head bent industriously over a much-scarred walnut desk. Light played over the paper, too--three sheets, closely written--and over a squat ink bottle tilted on a silver compact so that the faded black yield might be sufficient to moisten the blunt tip of a pen which many fingers had grasped.

The fingers which held it now were lovely, tapering to tips of pearl. Only one smudge marred their gentle perfection as the writer penned, "All my love, Betty."

Betty and her friend Loys Lester are sharing a hotel room, and much is made of the contrast between the blonde, glamorous Betty and dark, less rumple-proof Loys. And then there are inadvertently slashy lines like, "Considering Loys in her serviceable slip and her woolly brown cardigan, Betty grinned impishly--but swiftly, with an effort, she subdued herself and approached the bed." Or is that just me? Anyway, Betty is spotless and perfect, hard-working and even-tempered. She and Loys, a Hollywood reporter, are on vacation, during which Betty keeps getting recognized. She deals with this by denying she is Betty Grable, quite effectively it seems. But something seems amiss, and the vacation has lost some of its spontaneous luster.

It's all rather boring, really. The writing, I mean. Clothes are invariably described, characters are referred to by hair color, and Betty stops to think about scary cat noises and looming thunderclouds before dismissing her anxieties with a (usually) figurative toss of her head. She and Loys somehow get stranded with some mysterious strangers at a mansion, where they are accused of theft and locked in a bedroom, until the whole thing is solved because someone was pretending the house was haunted. It's all very Nancy Drew/Scooby-Doo. Then I skipped to the end, where they discuss their next destination (they've been folding up a map and pointing blindly to the next stop) and one of them points out the quilt on the neatly turned-down bed and says, "There's something about a patchwork quilt... Let's do our poking right there!"

Ginger Rogers and the Riddle of the Scarlet Cloak

Ginger Rogers is not Ginger Rogers. She looks like her, talks like her, but is in fact a switchboard operator at a fancy hotel. All the men who call up love that honeyed voice! Naturally, she has an unfortunate friend who... Look, I'm just going to transcribe the whole mess because it's the clearest expression of this I've seen in a long time. Her friend Patsy wants to know why she won't go out with guests:

Ginger smiled. "I notice you never go out when you're asked, either."

"What do you mean, when I'm asked?" Patsy wanted to know. "Nobody ever asks me and you know it. I'm too wide and too short. They forgot to give ma nose and my second chin's got more character than my first one. I'm pigeon-toed and my underskirt's always hanging and there's nothing I can do about it."

As Ginger's merry laugh rang out through the little room, Patsy added, "And the name's Patsy Potts! Remember?"

Dear, comical Patsy. You laughed with her not at her. She didn't really look as bad as she painted herself. That was why it was always funny when she picked herself to pieces for the entertainment of her friends. Patsy wasn't really "too wide and too short." She was just plump, in spots. "Yeah, all the wrong spots," Patsy would say. Her underskirt didn't always hang down, just at times, and usually when Patsy was trying to make a good impression. Patsy was pretty when she "fixed herself up." But best of all to Ginger, Patsy was a true-blue friend. She was devoted to Ginger--all her dreams of romance hovered about the head of her friend, rather than about her own.

SERIOUSLY, 1942. Anyone else feeling a little sorry for the real Ginger? Her mom raised her right, I guess. Anyway, chapter two starts with a bang, literally:

Something happened the very next day that changed the whole life of Ginger Rogers. It was also destined to change the lives of all Americans, of Englishmen, of Australians, of South Americans--and of all of the inhabitants of the civilized world!

Japan treacherously attacked Pearl Harbor while her envoys were talking peace in Washington!

1942, remember? Italics are so not mine. The French-born hotel owner calls her staff together to explain that they're sending all the guests away to open up instead for the use of aircraft workers so they can be comfy while they start churning out secret weapons. Madame DuLhut, after all, doesn't want the US to roll over and give up like France did. Happily, the entire staff--even the German pastry chef, Rogers hastens to assure us--approves of this plan. The Americans who were born here "were no more enthusiastic than those others who were America's adopted children." (I guess the Japanese don't count.)

Ginger and Mme. DuLhut discuss Ginger's mom's edict that she not date rich boys (who aren't interested in marrying working girls), Ginger receives the eponymous scarlet cloak anonymously, and mother worries about her accepting such a gift. Great pains are taken to express both that girls do grow up someday, and that Mary (not Lela) Rogers did a Herculean job of raising her daughter alone.

Ginger seems to have her pick of the men, despite her lowly status. And it seems one rich aircraft manufacturing man has got round her mother's prohibition, though she really wants Ginger to marry the boy down the street. But Miles takes her to a Hollywood premiere, insisting she wear the cloak, where a strange man "with the face of Satan" keeps staring at her and mysteriously exchanges a packet of cigarettes with Miles. None of which, of course, Miles admits. At a fancy restaurant, Miles leaves her alone to take care of something, and another resident of the hotel, playboy Gregg Phillips, takes her out on the dance floor. It was, apparently, love at first phone call, despite warnings from others (her mother most especially) that Gregg is not the type of man she should know.

Of course, Miles is found injured and passed out and Ginger is soon in over her head in some sort of espionage mystery. And love story. Only Mary Rogers is harboring a SECRET reason Ginger shouldn't see Gregg:

Again Mary Rogers experienced that appalling sense of inadequacy. She was not equal to such a problem. It was all so easy when Ginger was young and needed only foo and clothing and kindness. Now she needed a guiding hand, wise and patient, and Mary felt herself deficient in both qualities.

Not Shakespeare, sure, but interesting that her fictionalized spy story about her own daughter has so much of her mother in it--and how it veers between the perfection of their relationship and its (fictional) problems. Including hiding from Ginger the truth about her father--according to wikipedia, her parents separated shortly after her birth, and her father even kidnapped her twice. And it was her mother's influence that pushed her towards the stage and Hollywood. Wiki also reports that mother and daughter were close as long as Lela lived, and that Lela was a huge influence throughout Ginger's career. How much was Lela Rogers exorcising in this little novel? How did Ginger feel about it? What on earth is going on when a mother writes RPF about her daughter, including parental conflict, a love affair, and the mother's own marital issues?

Now that is the story I want to write.

Anyway, things continue apace, with Gregg and Ginger deciding to get married after one eventful evening, Mary tossing Gregg out of the house, and the nice-guy boyfriend Patsy thought not good enough for Ginger luckily turning out to be good enough for her. Ginger trusts whom she trusts (read: likes) and suspects those she doesn't. Good rule, when you're drawn into service of your country! There is talk of a "Fifth Columnist" and some lovely writing, such as the doozy: "Indeed, there was so much to tell and yet there was nothing really definite and tangible. Everything was indefinite and intangible--that is, simply 'sort of suspicious.'"

The real-life weirdness continues when Gregg reveals that he's known Ginger's dad, Josh, his whole life. Josh Rogers is with the FBI, lives clean, and was like a second father to Gregg--which is interesting, since he doesn't seem to have been a first father to Ginger. But he's a great man, honest! Especially exciting is the fact that in real life, "Rogers" was Ginger's step-father's name, though she was never technically adopted. In fantasy-land, Gregg thinks Mary's down on rich boys because Josh used to be rich and she suspects it spoiled him and ruined their relationship--though Gregg assures Ginger that Josh never stopped loving her mother. So. Ginger's fatherless state is due to a misunderstanding, and Rogers is her real dad.

In the end, Ginger catches the real spy through her switchboard know-how, and then totally inexplicably goes off alone with him before anyone else knows what she does. She's marginally clever throughout, but relies mostly on intuition and being saved by men. At least she is a "working girl," I guess. Happily, she's rescued, Mary and Josh have an off-screen reunion, and everything's cleared up pretty much on the last page.

In short: these books are not very good. Nor did they really need to be, if you think about it. And the fascination lies not in their quality, but their existence. How did people respond to the idea of RPF back then? Was this a common practice in movie mags of the time? Who authorized the use of these personae? I haven't found a link by studio or anything like that. And what else are we missing from the history of RPF, before it got a clever name? Does it even count as such, when no effort is made to make it "real" beyond the names and likenesses?

Ginger Rogers and the Riddle of the Scarlet Cloak by Lela E. Rogers, and

Betty Grable and the House with the Iron Shutters by Kathryn Heisenfelt.

What is RPF, you may well ask?

RPF stands for "real person fanfiction," a subset of fanfic which, instead of fictional characters, takes as its subjects actual people, usually celebrities. In the past few decades there's been a lot of angst in fan communities about the ethics of this sort of activity, and the degree to which it violates an actor or musician's right to privacy. What's fascinating about this find is the reminder that, well, it's been around a lot longer than fanfiction.net.

So what are these books like? The full text of title page for the Ginger Rogers one continues:

GINGER ROGERS

famous motion-picture star

as the heroine

By LELA E. ROGERS

Illustrated by Henry E. Vallely

Authorized Edition

WHITMAN PUBLISHING COMPANY

RACINE, WISCONSIN

The verso includes: Except the authorized use of the name of Ginger Rogers, all names, events, places, and characters in this book are entirely fictitious.

I was, understandably, fascinated, so I bought them both, put them on my shelf, and promptly forget about them. Until now. Looking at them, they're that very lightweight, cheap sort of thing that I doubt would have held up in a library setting for long. I do wonder where these copies came from. (Betty Grable shows 38 copies on www.abe.com, from $3.00 to $78.97; Ginger Rogers shows 63 copies from $2.15 to $110.12, if you're curious.) The back pages list charming titles from the same publisher, segregated for girls and boys, though the page of interest reads thus:

WHITMAN AUTHORIZED EDITIONS

NEW STORIES OF ADVENTURE AND MYSTERY

Up-to-the-minute novels for boys and girls about Favorite Characters, all popular and well-known, including--

Ginger Rogers and the Riddle of the Scarlet Cloak

Deanna Durbin and the Adventure of Blue Valley

Deanne Durbin and the Feather of Flame

Ann Rutherford and the Key to Nightmare Hall

Blondie and Dagwood's Secret Service

Polly the Powers Model: The Puzzle of th Haunted Camera

Jane Withers and the Hidden Room

Bonita Granville and the Mystery of Star Island

Joyce and the Secret Squadron: A Captain Midnight Adventure

Nina and Skeezix (of "Gasoline Alley"): The Problem of the Lost Ring

Red Ryder and the Mystery of the Whispering Walls

Red Ryder and the Secret of Wolf Canyon

Smilin' Jack and the Daredevil Girl Pilot

April Kane and the Dragon Lady: A "Terry and the Pirates" Adventure

(It also mentions that "The books listed above may be purchased in the same store where you bought this book." Oh, if only that were true! Note, by the way, the fact that actresses, not the roles they play, share "Favorite Character" status with comic strip figures. In the case of most of these stars, that's probably fairly accurate.)

This website has a complete listing of the actress titles, which also include Judy Garland, Shirley Temple, Gene Tierney, and Dorothy Lamour. It also reveals that Lela E. Rogers was Ginger's mother, and lots of other stuff I don't have access to, like general information about the writing and the way in which the "real person" angle is handled. According to the site, Heisenfelt wrote half the books, all of which "read like parodies of series books":

Heisenfelt's characters nearly always encounter one or more people who are stricken by fear that is superstitious. The heroine is usually fearful as well, with the difference being that the heroine is able to control her fear enough not to make a complete fool out of herself. Every event in the story has a mysterious importance, and normal, everyday sounds, such as a shutting door or a cat's meow, are often taken to be extremely scary. The mystery usually turns out to be a fairly insignificant mystery, and in some cases would not have been a mystery had everyone communicated with each other. In short, Heisenfelt's books tend to be overly-dramatic. The entire plot of each Heisenfelt book usually occurs in a very short period of time, often in fewer than 24 hours.

It also explains that there are two groups of stories in this loosely-defined "series": books in which the main character is in fact the actress named, and "while the heroine is identified as a famous actress, the stories are entirely fictitious and center around a mystery that convenient appears while the heroine is briefly visiting a dear friend. In some of these stories, many of the other characters fail to recognize the actress in spite of her openness about her identity!" The others are adventures where the character has the same name and looks as the actress but is, in fact, just a regular girl. Since I have one of each here, I'll see what I can see without actually reading them cover to cover.

Betty Grable and the House With the Iron Shutters

The story opens:

An April sun which had made several ineffectual attempts to appear from behind a bank of sullen clouds met suddenly with a measure of success. Long streamers of light penetrated the mended laces of a tall window, twining in a caressing halo on the golden head bent industriously over a much-scarred walnut desk. Light played over the paper, too--three sheets, closely written--and over a squat ink bottle tilted on a silver compact so that the faded black yield might be sufficient to moisten the blunt tip of a pen which many fingers had grasped.

The fingers which held it now were lovely, tapering to tips of pearl. Only one smudge marred their gentle perfection as the writer penned, "All my love, Betty."

Betty and her friend Loys Lester are sharing a hotel room, and much is made of the contrast between the blonde, glamorous Betty and dark, less rumple-proof Loys. And then there are inadvertently slashy lines like, "Considering Loys in her serviceable slip and her woolly brown cardigan, Betty grinned impishly--but swiftly, with an effort, she subdued herself and approached the bed." Or is that just me? Anyway, Betty is spotless and perfect, hard-working and even-tempered. She and Loys, a Hollywood reporter, are on vacation, during which Betty keeps getting recognized. She deals with this by denying she is Betty Grable, quite effectively it seems. But something seems amiss, and the vacation has lost some of its spontaneous luster.

It's all rather boring, really. The writing, I mean. Clothes are invariably described, characters are referred to by hair color, and Betty stops to think about scary cat noises and looming thunderclouds before dismissing her anxieties with a (usually) figurative toss of her head. She and Loys somehow get stranded with some mysterious strangers at a mansion, where they are accused of theft and locked in a bedroom, until the whole thing is solved because someone was pretending the house was haunted. It's all very Nancy Drew/Scooby-Doo. Then I skipped to the end, where they discuss their next destination (they've been folding up a map and pointing blindly to the next stop) and one of them points out the quilt on the neatly turned-down bed and says, "There's something about a patchwork quilt... Let's do our poking right there!"

Ginger Rogers and the Riddle of the Scarlet Cloak

Ginger Rogers is not Ginger Rogers. She looks like her, talks like her, but is in fact a switchboard operator at a fancy hotel. All the men who call up love that honeyed voice! Naturally, she has an unfortunate friend who... Look, I'm just going to transcribe the whole mess because it's the clearest expression of this I've seen in a long time. Her friend Patsy wants to know why she won't go out with guests:

Ginger smiled. "I notice you never go out when you're asked, either."

"What do you mean, when I'm asked?" Patsy wanted to know. "Nobody ever asks me and you know it. I'm too wide and too short. They forgot to give ma nose and my second chin's got more character than my first one. I'm pigeon-toed and my underskirt's always hanging and there's nothing I can do about it."

As Ginger's merry laugh rang out through the little room, Patsy added, "And the name's Patsy Potts! Remember?"

Dear, comical Patsy. You laughed with her not at her. She didn't really look as bad as she painted herself. That was why it was always funny when she picked herself to pieces for the entertainment of her friends. Patsy wasn't really "too wide and too short." She was just plump, in spots. "Yeah, all the wrong spots," Patsy would say. Her underskirt didn't always hang down, just at times, and usually when Patsy was trying to make a good impression. Patsy was pretty when she "fixed herself up." But best of all to Ginger, Patsy was a true-blue friend. She was devoted to Ginger--all her dreams of romance hovered about the head of her friend, rather than about her own.

SERIOUSLY, 1942. Anyone else feeling a little sorry for the real Ginger? Her mom raised her right, I guess. Anyway, chapter two starts with a bang, literally:

Something happened the very next day that changed the whole life of Ginger Rogers. It was also destined to change the lives of all Americans, of Englishmen, of Australians, of South Americans--and of all of the inhabitants of the civilized world!

Japan treacherously attacked Pearl Harbor while her envoys were talking peace in Washington!

1942, remember? Italics are so not mine. The French-born hotel owner calls her staff together to explain that they're sending all the guests away to open up instead for the use of aircraft workers so they can be comfy while they start churning out secret weapons. Madame DuLhut, after all, doesn't want the US to roll over and give up like France did. Happily, the entire staff--even the German pastry chef, Rogers hastens to assure us--approves of this plan. The Americans who were born here "were no more enthusiastic than those others who were America's adopted children." (I guess the Japanese don't count.)

Ginger and Mme. DuLhut discuss Ginger's mom's edict that she not date rich boys (who aren't interested in marrying working girls), Ginger receives the eponymous scarlet cloak anonymously, and mother worries about her accepting such a gift. Great pains are taken to express both that girls do grow up someday, and that Mary (not Lela) Rogers did a Herculean job of raising her daughter alone.

Ginger seems to have her pick of the men, despite her lowly status. And it seems one rich aircraft manufacturing man has got round her mother's prohibition, though she really wants Ginger to marry the boy down the street. But Miles takes her to a Hollywood premiere, insisting she wear the cloak, where a strange man "with the face of Satan" keeps staring at her and mysteriously exchanges a packet of cigarettes with Miles. None of which, of course, Miles admits. At a fancy restaurant, Miles leaves her alone to take care of something, and another resident of the hotel, playboy Gregg Phillips, takes her out on the dance floor. It was, apparently, love at first phone call, despite warnings from others (her mother most especially) that Gregg is not the type of man she should know.

Of course, Miles is found injured and passed out and Ginger is soon in over her head in some sort of espionage mystery. And love story. Only Mary Rogers is harboring a SECRET reason Ginger shouldn't see Gregg:

Again Mary Rogers experienced that appalling sense of inadequacy. She was not equal to such a problem. It was all so easy when Ginger was young and needed only foo and clothing and kindness. Now she needed a guiding hand, wise and patient, and Mary felt herself deficient in both qualities.

Not Shakespeare, sure, but interesting that her fictionalized spy story about her own daughter has so much of her mother in it--and how it veers between the perfection of their relationship and its (fictional) problems. Including hiding from Ginger the truth about her father--according to wikipedia, her parents separated shortly after her birth, and her father even kidnapped her twice. And it was her mother's influence that pushed her towards the stage and Hollywood. Wiki also reports that mother and daughter were close as long as Lela lived, and that Lela was a huge influence throughout Ginger's career. How much was Lela Rogers exorcising in this little novel? How did Ginger feel about it? What on earth is going on when a mother writes RPF about her daughter, including parental conflict, a love affair, and the mother's own marital issues?

Now that is the story I want to write.

Anyway, things continue apace, with Gregg and Ginger deciding to get married after one eventful evening, Mary tossing Gregg out of the house, and the nice-guy boyfriend Patsy thought not good enough for Ginger luckily turning out to be good enough for her. Ginger trusts whom she trusts (read: likes) and suspects those she doesn't. Good rule, when you're drawn into service of your country! There is talk of a "Fifth Columnist" and some lovely writing, such as the doozy: "Indeed, there was so much to tell and yet there was nothing really definite and tangible. Everything was indefinite and intangible--that is, simply 'sort of suspicious.'"

The real-life weirdness continues when Gregg reveals that he's known Ginger's dad, Josh, his whole life. Josh Rogers is with the FBI, lives clean, and was like a second father to Gregg--which is interesting, since he doesn't seem to have been a first father to Ginger. But he's a great man, honest! Especially exciting is the fact that in real life, "Rogers" was Ginger's step-father's name, though she was never technically adopted. In fantasy-land, Gregg thinks Mary's down on rich boys because Josh used to be rich and she suspects it spoiled him and ruined their relationship--though Gregg assures Ginger that Josh never stopped loving her mother. So. Ginger's fatherless state is due to a misunderstanding, and Rogers is her real dad.

In the end, Ginger catches the real spy through her switchboard know-how, and then totally inexplicably goes off alone with him before anyone else knows what she does. She's marginally clever throughout, but relies mostly on intuition and being saved by men. At least she is a "working girl," I guess. Happily, she's rescued, Mary and Josh have an off-screen reunion, and everything's cleared up pretty much on the last page.

In short: these books are not very good. Nor did they really need to be, if you think about it. And the fascination lies not in their quality, but their existence. How did people respond to the idea of RPF back then? Was this a common practice in movie mags of the time? Who authorized the use of these personae? I haven't found a link by studio or anything like that. And what else are we missing from the history of RPF, before it got a clever name? Does it even count as such, when no effort is made to make it "real" beyond the names and likenesses?

The Man Who Wasted an Opportunity

Posted by Kris/Pepper at 10:54 AM Labels: film

[Light spoilers for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote]

I don't want to be too hard on Terry Gilliam.

The guy's obviously gone through a lot in his attempts to adapt Don Quixote for the past nearly 30 years, and it's evidently a miracle The Man Who Killed Don Quixote even made it to theaters for me to see. And it's fun, it's interesting in places, it has lovely performances, and I think it thinks it's saying something about the nature of identity and storytelling and filmmaking. It's about a commercial director who once made a student film about Don Quixote, who travels to the same village years later to learn that the man he'd plucked from shoe-making obscurity to play the lead is now convinced he is the medieval knight, and recruits the director as his squire, Sancho Panza. "Wow, that's meta," I hear you say. The thing is, it's not nearly meta enough.

If you're unfamiliar with the story of Don Quixote, the original is a novel by Miguel de Cervantes from the early 1600s about a scholar who reads too many chivalric romances and decides to go knight-erranting as Don Quixote. He sees the world as he believes it should be, and thus he fights windmills he believes to be giants and rescues prostitutes he believes to be damsels. Much of the cultural legacy of Quixote is in the value of a certain type of madness, an attempt to turn an excess of realism on its head and celebrate a worldview that has an influence by being the change it wants to see. So naturally, it is ripe for metatextual play, and in fact the film version of the musical Man of La Mancha embeds the tale in a framing narrative of Cervantes telling the story himself while imprisoned, as a means of inspiring in a time of political upheaval.

So in a film that is about an actor who believes he IS Quixote, who inveigles a wayward film director into being his squire, I saw opportunity for a wide ranging commentary on storytelling, filmmaking, the line between the narratives we tell ourselves and madness, and Gilliam's own journey in trying to make this very film. It seems made for that kind of story in a way something like Adaptation frankly was not, in the sense that the very narrative he's trying to adapt bring reality and storytelling into sharp relief. It was an opportunity to do something like 2005's Tristram Shandy, itself based on another PoMo-before-Modern-was-even-a-thing novel by Laurence Sterne in which the nature of adapting the unadaptable is faced head-on. I don't mean that The Man Who Killed Don Quixote had to be deep, but I did expect it to actually make use of the elements it had set up.

But apart from having adapted Quixote, there is almost no connection between the filmmaker, Toby (played by an always exceptional Adam Driver), and the themes of madness and storytelling. At least, not in the sense that the film ever seems to get around to saying anything about his position in society as a teller of stories. And while Jonathan Pryce is a very good Quixote, we never really learn anything about what embodying this fictional knight has done for his life or his sense of self. In fact, I know no more about the characters of the original OR the adaptation than I did at the beginning. It's a romp, to be sure, and not unenjoyable. But when the very text you're adapting contains such rich fodder for an exploration of the value of telling tales, it seems remarkable un-self-aware.

I don't want to be too hard on Terry Gilliam.

The guy's obviously gone through a lot in his attempts to adapt Don Quixote for the past nearly 30 years, and it's evidently a miracle The Man Who Killed Don Quixote even made it to theaters for me to see. And it's fun, it's interesting in places, it has lovely performances, and I think it thinks it's saying something about the nature of identity and storytelling and filmmaking. It's about a commercial director who once made a student film about Don Quixote, who travels to the same village years later to learn that the man he'd plucked from shoe-making obscurity to play the lead is now convinced he is the medieval knight, and recruits the director as his squire, Sancho Panza. "Wow, that's meta," I hear you say. The thing is, it's not nearly meta enough.

If you're unfamiliar with the story of Don Quixote, the original is a novel by Miguel de Cervantes from the early 1600s about a scholar who reads too many chivalric romances and decides to go knight-erranting as Don Quixote. He sees the world as he believes it should be, and thus he fights windmills he believes to be giants and rescues prostitutes he believes to be damsels. Much of the cultural legacy of Quixote is in the value of a certain type of madness, an attempt to turn an excess of realism on its head and celebrate a worldview that has an influence by being the change it wants to see. So naturally, it is ripe for metatextual play, and in fact the film version of the musical Man of La Mancha embeds the tale in a framing narrative of Cervantes telling the story himself while imprisoned, as a means of inspiring in a time of political upheaval.

So in a film that is about an actor who believes he IS Quixote, who inveigles a wayward film director into being his squire, I saw opportunity for a wide ranging commentary on storytelling, filmmaking, the line between the narratives we tell ourselves and madness, and Gilliam's own journey in trying to make this very film. It seems made for that kind of story in a way something like Adaptation frankly was not, in the sense that the very narrative he's trying to adapt bring reality and storytelling into sharp relief. It was an opportunity to do something like 2005's Tristram Shandy, itself based on another PoMo-before-Modern-was-even-a-thing novel by Laurence Sterne in which the nature of adapting the unadaptable is faced head-on. I don't mean that The Man Who Killed Don Quixote had to be deep, but I did expect it to actually make use of the elements it had set up.

But apart from having adapted Quixote, there is almost no connection between the filmmaker, Toby (played by an always exceptional Adam Driver), and the themes of madness and storytelling. At least, not in the sense that the film ever seems to get around to saying anything about his position in society as a teller of stories. And while Jonathan Pryce is a very good Quixote, we never really learn anything about what embodying this fictional knight has done for his life or his sense of self. In fact, I know no more about the characters of the original OR the adaptation than I did at the beginning. It's a romp, to be sure, and not unenjoyable. But when the very text you're adapting contains such rich fodder for an exploration of the value of telling tales, it seems remarkable un-self-aware.

Another review from a Trekkie who didn’t love Discovery. How original!

Posted by Kris/Pepper at 3:38 PM Labels: star trek, tv

This week, as everyone was freaking out about Game of Thrones, I finished season 2 of Star Trek: Discovery. Ever since, I’ve been debating how to write this, and why. It’s important to me that I love Star Trek, in its myriad forms. I’ve ruled out wanting a rehash of the old show, just as I’ve ruled out many of the reasons my facebook group is full of salt. But I am trying to understand just what isn’t working for me, so that’s what this is going to be about.

The truth is, I have NOT loved every iteration of Trek instantly. Deep Space Nine is probably my favorite (tied with the original), though I find the first season almost unwatchable. I adore Voyager, but it took me awhile to get into. I never did manage to warm to Enterprise, which I thought had some good ideas and characters and design but failed to capture the spirit I wanted. And that’s generally how I feel about Discovery: that it’s trapped between two forms of television storytelling and has many great ideas that are foundering in their execution. Overall, it feels like something that is playing it too safe, even as it takes great strides to demonstrate the diversity that should be evident throughout any Trek franchise.

But while the diversity is well shown, I find most of the actual writing to lean heavily on telling. We are told, over and over, how hard things are for characters. Or how important something is. I love the trials that are set up for the characters, the identity-shaking, life and love and death situations, the notion that we are here to make the galaxy better. But I hardly ever feel those conflicts. This is more evident in the voiceover narration, which is tediously high-school diary. (“Just as repetition reinforces repetition, change begets change....Sometimes the only way to find out where you fit in is to step out of the routine. Because sometimes, where you really belong was waiting right around the corner all along.”) But it happens between characters, too, as Spock looks meaningfully at a three-dimensional chess set and intones, “the board is yours, Michael.”

So what am I missing? I don’t think any of the previous series are or should be a model for a new Trek. Nor do I think Trek needs to hare off into some new grimdark territory to keep up with Breaking Bad or Game of Thrones or the fake-gritty DCU. What I do think we have, here, is an attempt to have both of those things that accomplishes neither. An attempt at the old feeling (including Spock and Pike, references to uniform color, etc) while trying too hard to be profound and edgy. But the cake-and-eat-it-too attempt to hew close to established canon while doing something new and different neither feels like canon nor like anything original and fresh. It feels constrained by creators who are afraid to step too far outside two boxes that don’t have a lot of overlap. And you get a show that should be helmed by the women and actors of color who hold most of the parts, but relies on Pike and Spock for a lot of the emotional core. You get a show that doesn’t bother to tell me why I should care about Airiam until she’s dead. A show that thinks it needs Section 31 and the mirror universe to provide edge and conflict.

We can argue about what Star Trek is, what elements make something “feel like” Trek. And I’ve quarreled with new interpretations before. But it’s not so much that I need Discovery to BE like DS9 or Voyager. It’s that I want it to stop feeling like it wants to be Star Wars or Mass Effect without making Trekkies mad. I want it to explore what it means to be human, or anyway part of the collective the Federation has and will become. I want it to offer a dose of optimism that we will choose to do better. And I want it to take risks. I don’t want a show with a plodding arc that literally takes us to a point where it writes itself out of existence, simply because they’ve trapped themselves in a time frame that is unworkable with the story they want to tell. If you wanted a show that doesn’t fit with the timeline or the technology already set up, maybe you aren’t writing the right show. I’m not asking for The Original Series Two. But I am saying that by wrapping itself up in a time period and with existing characters whose fates are already known, it’s constrained itself out of any sense of momentum or progress.

I am hoping that, next season, this show will come into its own. There are big plot indications it might well do that. But for the first few seasons, I feel that Discovery has been hampered by a slavish attempt to replicate the wrong things about Star Trek. I hope it finds new life soon.

Labels

Blog archive

About Me

Powered by Blogger.

What is this?

My name is Kris or Pepper, and I write about film, fandom, and life as an aging pixie in Seattle.

Powered by WordPress

©

Pepper on Everything - Designed by Matt, Blogger templates by Blog and Web.

Powered by Blogger.

Powered by Blogger.